Lasting legacy of redlining joins new abandonment of lower income Iowans

Des Moines exhibit highlights the challenges finding decent, affordable housing

A recent two-week exhibit inside, of all places, a former shipping container on the grounds of Des Moines’ Harkin Institute, offered stark rebuttals to stereotypes about Iowans who need government help to make ends meet. That population has become a popular target of political rhetoric and punitive actions by those looking to expand tax cuts for billionaires. It’ll soon face new work requirements to receive Medicaid and increased ones to get on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, which is slated for $230 billion in cuts over 10 years.

The exhibit reveals the extent of economic hardship faced by even full-time workers in Des Moines who can’t find or afford housing. And it illustrates how the legacy of a historical form of housing discrimination that destroyed once thriving Black homes and neighborhoods continues to play out today.

Uplift examined Asset-Limited Income-Constrained Employment (ALICE) to determine that 37 % of Iowans – 482,779 people – live $16,000 a year below the income threshold for survival. That’s factoring in monthly expenses for a family of two working parents and two children. It would take full-time hourly wages of $42. 83 apiece ($85,656 a year) to meet their needs.

Among the workers struggling to meet basic needs are nursing assistants, 38% of whom live below the ALICE threshold, earning on average $37,336 a year; retail salespeople, (22%), earning $29,910; and fast-food workers who earn on average $28,329, with 63% living below the threshold.

The National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC) calls Iowa one of four Midwestern states where minimum wages don’t support rent. In a July 17 report it says “the housing wage” should be $20 an hour to afford spending 30% on a decent two-bedroom rental home. The average tenant here makes $17.32 an hour, though Iowa’s minimum wage is stuck at a pathetic $7.25.

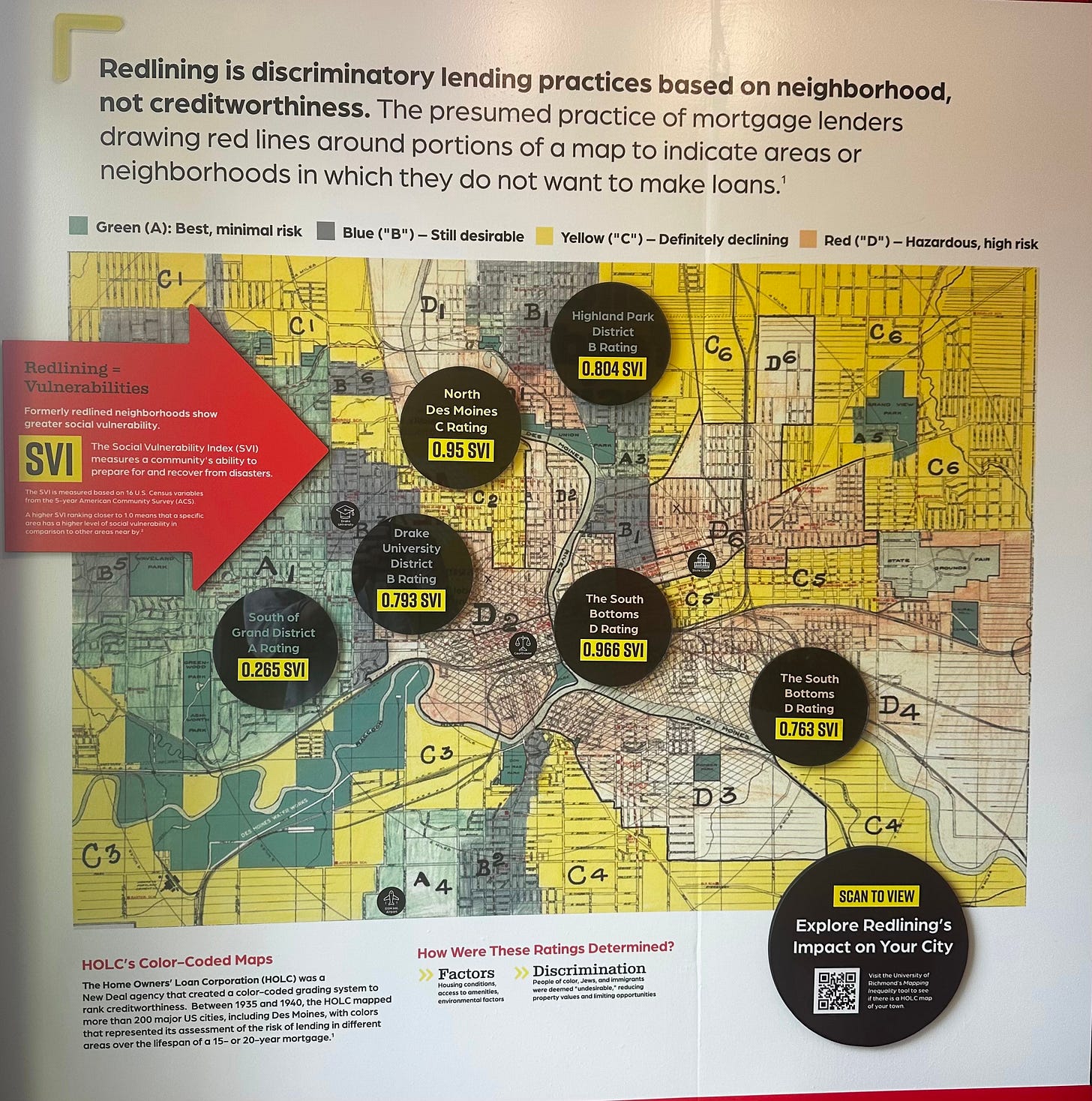

The exhibit’s other focus – racial discrimination in housing - looks at the impact of “redlining” in Black neighborhoods between 1935 and 1940 as a likely key determinant of current economic and social inequality. Under that practice, home loan decisions were based not on credit worthiness but neighborhood and demographics – namely where Black people lived. The Homeowners Loan Corp. drew color-coded lines on a map around neighborhoods in more than 200 U.S. cities to assess the risks of making loans. Those were then graded from A to D based on general housing conditions, access to amenities and environmental factors unrelated to the particular home. In Des Moines, South of Grand neighborhoods were rated A Southeast Bottoms scored D.

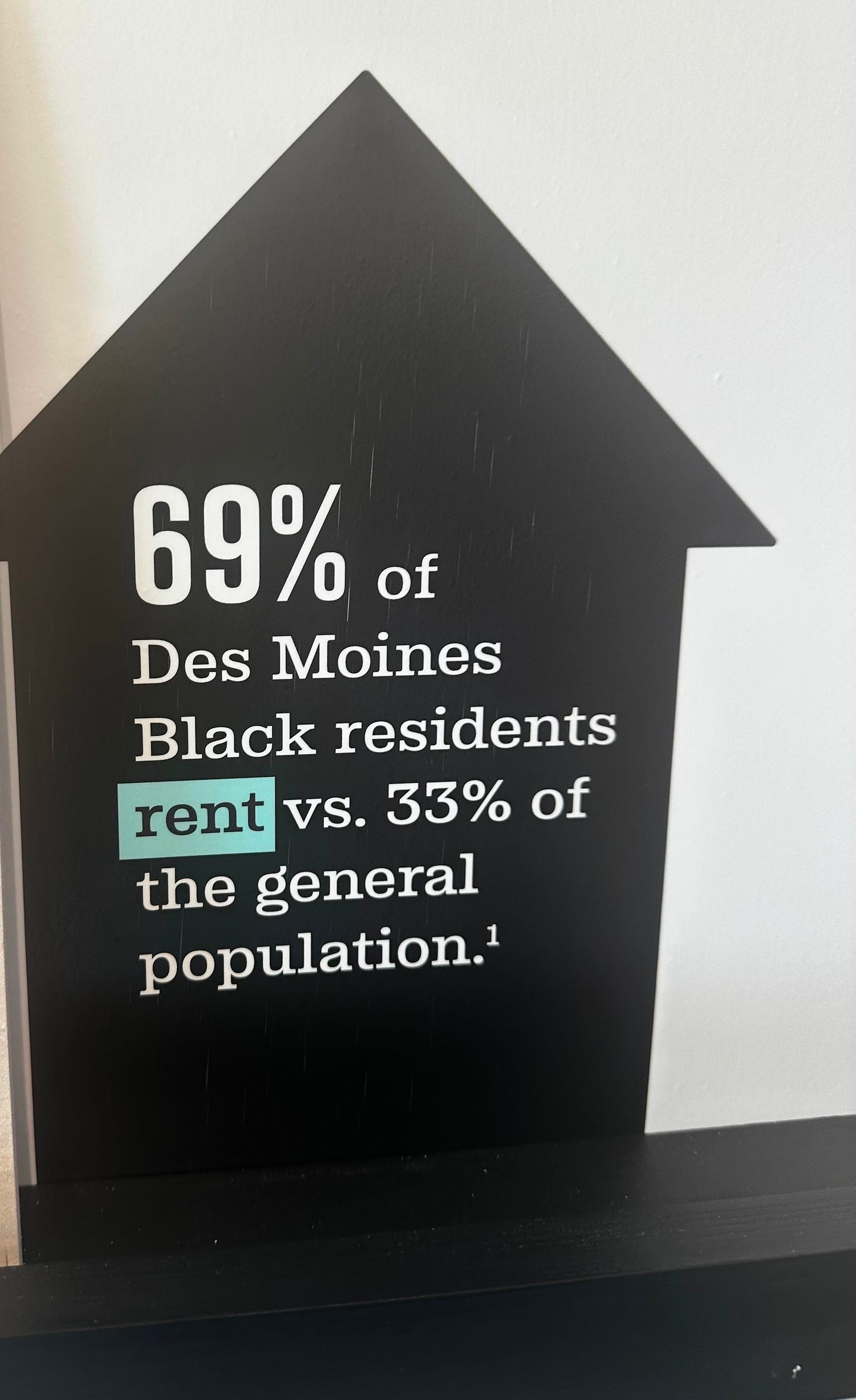

Still today Black applicants are 2.2 times more likely to be denied home loans in Greater Des Moines than the general population; 69% of Black Des Moines residents rent rather than own their homes, compared to 33% of the general population. And formerly redlined areas of Des Moines have the highest concentrations of low-income people, more vulnerable in their ability to prepare for and recover from disasters.

“People of color are significantly more likely than white people to experience evictions and homelessness in the United States,” says the NLIHC website, “the result of centuries of structural racism that continues today…”

Other discriminatory practices in Des Moines included the construction of the MacVicar Freeway in the 1960s – now I-235 – that enabled movement to the suburbs from downtown, while cutting through predominantly Black middle-class neighborhoods. Center Street, which had Black-owned homes, businesses and entertainment centers was one victim.

And urban renewal policies, depicted as efforts to revitalize decaying areas, actually led to the seizure and demolition of Black-owned homes. As a 1973 Des Moines Register article in the exhibit described, developers might tell a family their old house was worth far less than its tax assessment of $7500, and give them $5000 to move out – then sell the land. That wouldn’t pay for even a moderate quality home; many families were forced into public housing. And since housing is a key source of accrued wealth, successive generations missed out.

Today a median 1-bedroom rental in Iowa costs $949 -- $1,113 in Polk County.

Statewide in Iowa, there are only 38 affordable, available units per 100 very low-income households, the exhibit shows.

And then there’s eviction: In Iowa, 69 % of evictees are women. The single greatest predictor of an eviction, according to Matthew Desmond of Princeton University, is a child in the household. Black people are 41 % of those evicted and people with disabilities are 39 %.

Homelessness, which was experienced by nearly 8,000 people in Polk County in 2024, has since increased 9%. On any given night in Polk County, 715 people are sleeping outside.

Against these discouraging statistics are sources of hope and action. Though half of all evictions are dismissed without court action, in Iowa they remain on a person’s record forever, and show up on background checks. Iowa should do eviction expungements like some other states.

A bright light on the housing landscape is the nonprofit Central Iowa Community Land Trust. It provides entry level housing by preserving existing houses and reselling them affordably. It owns the land; the resident owns the house. That lowers the cost of mortgage payments and deposits by about a third. Growing CLT funds buy more affordable housing.

And Habitat for Humanity builds homes for sale below market interest rateswith affordable mortgages, capping monthly payments at 30% of income.

Asked what Iowans can do to help the housing shortage, Carrie Woerdeman executive director of the nonprofit Home Inc., which aims to increase access to safe, stable, affordable housing, urged fighting NIMBY-ism. She calls the “Not in My Back Yard” attitude, based largely on stereotypes about renters or those of lower income – “one of the most significant challenges to new affordable housing projects.” She also suggests advocating with state and federal officials for more rental assistance and for HUD and low income housing tax credits, and volunteering with nonprofit housing organizations.

And it’s past time that Iowa’s joke of a minimum wage was raised to a livable one, that funding cuts to unemployment benefits were restored, along with unemployment business taxes. That means challenging a mindset expressed by Iowa’s governor, in a 2022 speech: "When idleness is rewarded with an unemployment check, work begins to seem optional rather than fundamental. Then society begins to decay."

Maybe the real decay comes when public officials write off those of lesser means and strain to justify it.

I’m a proud member of the Iowa Writer’s Collaborative. Click below for the full roster.

Your willingness to expose the hypocrisy and degradation of morality imbued within our elected officials is exemplary. Just once I’d like to see one of these haughty, penurious politicians (who were born on third base and believe they hit a triple) try living on what they expect others to do. They won’t and couldn’t care less. Thanks for your service and intrepid reporting, as always Rekha Basu.

Thank you for this vital report, Rekha